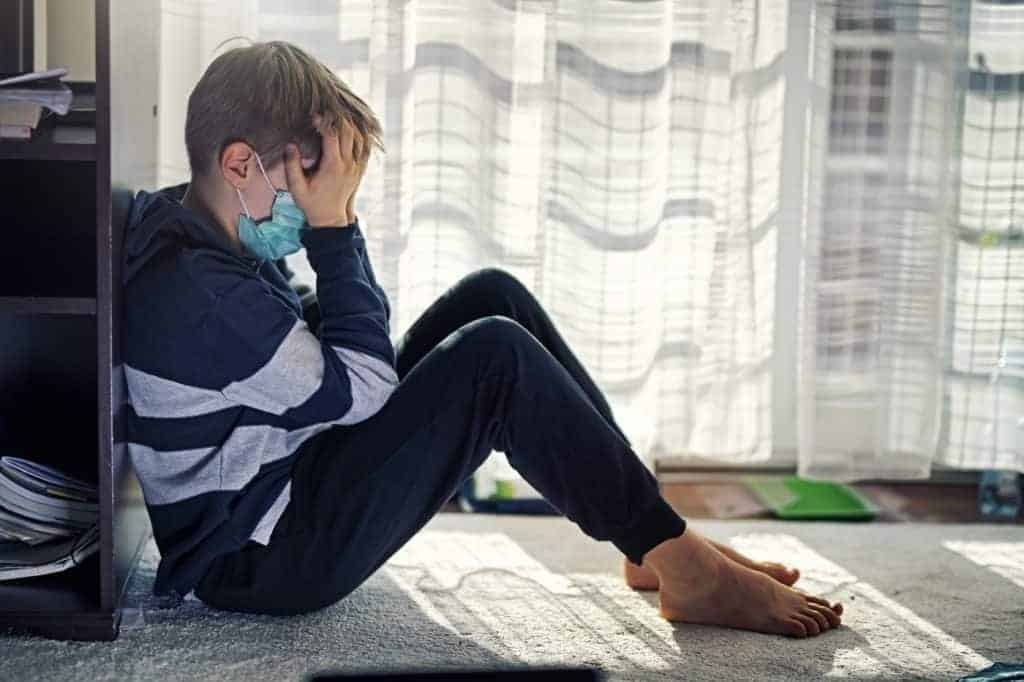

Families are the first and best line of defence for their loved ones. They support, lead, advocate and often bear the burden of ensuring their loved ones living with mental illness get the help they need.

However, it can be difficult to watch those we love struggling with various health challenges and as a result taking a toll on our own mental health and well-being. We often experience uncertainty, fear, frustration and helplessness because we want to fix it for those we care about. During this time, it is important to remember that your own health is important and if we are not taking care of ourselves, it will become difficult to be there for others.

Mental Health & Mental Illness

How has your life changed by your family member’s mental illness?

Mental illnesses have a significant impact on the family. To begin with, they may face difficult decisions about treatment, hospitalization, [and] housing… The individuals and their families face the anxiety of an uncertain future and the stress of what can be a severe and limiting disability. The heavy demands of care may lead to burnout… The cost of medication, time off work, and extra support can create a severe financial burden for families. Both the care requirements and the stigma attached to mental illness often lead to isolation of family members from the community and their social support network…

A Report on Mental Illness in Canada, Health Canada

When we first learn that a family member is living with a mental illness, we may experience a number of emotions including shock, fear, sadness, guilt, anxiety, confusion, compassion, understanding and even anger. Some are relieved to finally learn a reason for the changes they see, others hope that the diagnosis is wrong or that there has been some mistake. Family members may experience anger and resentment if they feel powerless in changing the situation for those they care about.

The challenges that mental illness brings affect the entire family—parents, spouses, siblings and children—both young and adult. One of the first steps we can take towards positively responding to those challenges is to learn more about what these experiences mean for both the individual and ourselves as the family member.

More information:

- CMHA National

- Adult Family Program (Registration required) Provides educational groups and individual support for families affected by someone else’s mental illness, substance use/abuse and /or gambling concerns. Please contact Mental Health and Addiction Services at 306-655-7777 and ask to be connected with an Adult Family Counsellor.

- Supporting a friend or family member with a mental illness

What are some of the emotions you are experiencing?

We sometimes feel like we are riding an emotional roller-coaster—when a loved one is doing well they’re hopeful and optimistic and when they relapse, we are often devastated.

It is important to remember that everyone’s experiences are different, this does mean they are worst or better, more or less than, it is the reassurance that supporting our loved ones can sometimes be challenging, it is normal to have a wide range of emotions.

Sometime we feel…….

ANGER

Among family members, anger is often the byproduct of love and hate relationships. Family members care for their loved one who is unwell, but they hate the painful experiences everyone goes through as a result. Painful events evoke anger and resentment towards the family member. It becomes increasingly difficult to separate the illness from the person.

SHAME

Because of the painful experiences, that result from the behavior of the loved one who is struggling the family feels ashamed of him/her. As the situation in the family worsens, the experience of shame increases. Not only are the family members ashamed of the person who is unwell, they become ashamed of the entire family, themselves included. Shame, in turn, produces feelings of low self-worth in each member of the family.

GUILT

The family members begin to blame themselves and one another for their painful experiences. Each family member may secretly feel that he or she is responsible for the illness. They tell themselves, “If only I could change, everything would be all right.” Such self-blame produces more feelings of guilt and shame.

HURT

Emotional pain can be broad and deep. It is painful to see a loved one deteriorate as mental illness worsens. It hurts to become involved in arguments, or to witness angry exchanges between other members of the family. Many times the person who is unwell blames others for his/her illness. Messages such as, “If you wouldn’t nag, I would be better,” or, “Do you know why I am the way I am? Look in the mirror!” cause deep emotional hurt. They also deepen the feelings of guilt and shame. The ill person is not interested in, or incapable of meeting the emotional needs of the rest of the family. This also results in hurt.

FEAR

Living in a constantly shifting and distressed family produces fear. There is fear of arguments, fear of financial problems, fear about the person’s illness, and fear of relapse. Perhaps there is even fear that everything will remain the same or fear of the future, fear of what will happen to the family if things continue to deteriorate. Fear becomes the dominating factor in the family’s interactions.

LONELINESS

Stressful family situations result in the breakdown of normal, rewarding family communication. Family love and concern are lost in the stress and crises of day-to-day living. Isolation is produced by the lack of healthy communication in the family. This results in more loneliness for everyone.

ABANDONMENT

The family members may be abandoned for days or weeks at a time. Not only does the abandonment occur physically, but also emotionally as well. This causes tremendous pain for the family members. It fuels feelings of fear, anger, humiliation and hopelessness.

PHYSICAL ABUSE

In many families, physical abuse by the person who is unwell is commonplace. The family becomes terrified of the brutality and unpredictability. Physical abuse increases the strongholds of fear, hatred and bitter judgement in the family members.

Coping with Your Feelings

When we are faced with challenges as family members we don’t always know how to respond, sometimes we choose not to respond, we frequently ask ourselves if we are making the right decision. Our emotions play a significant role in this process, we often respond out of hurt, fear or anger. Therefore we find ourselves on a journey of coping and learning how to cope with these challenges, below are some of the directions we may take:

- Denial: doing nothing about the problem in hopes that it will go away.

- Wishful thinking: doing nothing because you are sure that a miracle will occur, and the person experiencing a mental illness will change.

- Emotionality: reacting emotionally rather than remaining calm and thinking through logical solutions to your problem.

- Martyrdom: doing nothing because you cannot bear to hurt the person, which you may think is more important than your own feelings.

- Isolation: trying to handle the problem by yourself instead of asking for help.

Feeling Guilt? What to Do….

No matter how we decide to cope with the situation, it is difficult to remove the emotional connection we have when concerned about our family member, as a result we often are left feeling guilt. We consider every ‘shoulda, woulda, coulda’ you can imagine.

At times, we may feel guilty for putting ourselves first, for building resentment towards our loved ones (a sign of poor boundaries), for wishing life was how it use to be before the mental illness developed. It is ok to feel guilt, it becomes an issue when we allow it to control our life. Additionally, when an individual is experiencing mental illness, they lose their old identity and are forced to figure out who they are while managing their symptoms. This is the same for the family unit. What use to be is no longer, and this reality can be challenging, stressful, and devastating. Remember, you too are learning how to navigate this life and there is no expectation for you to know exactly what to do.

This sense of guilt or feeling guilty is our response to trying to balance the emotions we have and personal limits we try to set. This middle place leaves us conflicted in our decision making and problem solving about what is the best support we can provide to our family member living with a mental illness. What is important to remember is that you can both express your support and concern for them while firmly maintaining your personal limits.

Just because you feel guilty doesn’t mean you are guilty.

- Consider what your guilt is all about. Is it rational? Is it irrational? Is it about control?

- Talk it over with others. Though you don’t want people minimizing your feelings, talking about guilt can help you reflect.

- Examine your thoughts. Often our guilty thoughts, whether rational or irrational, start to consume us. They can drag us down into one of those bottomless black holes – the kind that are full of isolation, despair. In order to adjust your thinking, you have to know what your guilty thoughts are and notice them when they arise.

- If your guilty feelings are irrational, admit it. This doesn’t mean dismissing your feelings of guilt. It means acknowledging that, though you feel guilty, you may not actually be guilty. Some common examples are acknowledging you did the best you could with the information you had at the time, you couldn’t predict the future, there were many other factors at play other than your behaviors, etc. Being honest with yourself about your guilt is important.

- Forgive yourself. Easier said than done, right? Remember, forgiveness does not mean condoning or excusing. Forgiveness can mean accepting that we may have done something we regret but finding new attitude and perspective toward ourselves in relation to that action. It doesn’t mean we forget, but means we find a way to move forward.

- Figure out what you have learned. Guilt often teaches us something. It can be something about ourselves or about the world. We can learn and grow from almost any emotion (cheesy, but true) so take some time to consider what your guilt has taught you.

- Consider what your loved one would tell you. Get yourself in a space to truly focus on thinking about your loved one. Imagine telling them how you are feeling – your regrets, your guilt, all of it. If there are things you wish you had said, say them. Then imagine what your loved one would tell you.

Dealing with Stress & Burnout

The role of a family member is a significant source of support for an individual living with a mental illness, but the stress and challenges that arise can leave a family member feeling exhausted. What happens when we do not deal with this stress and exhaustion? The results could be conflict, broken relationships, and additional health concerns, this is called burnout and this is not where we want to be. As a family member we need to recognize when and how we reach out for support for ourselves.

Self – Care: Who is taking care of you?

Supporting a family member living with mental illness or experiencing mental health challenges can be both rewarding and stressful. For many, their biggest challenge is maintaining balance in our lives so that mental illness does not consume every minute of every day.

Stress is a natural part of life, but if not managed well, it can lead to your own health problems. When caring for someone living with a mental illness, family members have a tendency to put themselves as second priority. The most important thing to remember as a family member is to take care of YOU. The actions we take to maintain our own health and wellbeing are just as important.

Taking-Care-Of-Yourself.pdf (hamiltonhealthsciences.ca)

Healthy Altruism

Self-Care is as important as the care you provide for your unwell family member, particularly if they are living with you. Family members can feel over-loaded with the tasks and energy it takes to care for someone who is unwell. This support can be a stressful experience and you may feel many different emotions, as discussed in the previous section. In order to address this, we strongly recommend you adopt an attitude of healthy altruism rather than one of total sacrifice. Healthy altruism means being vigilant of your own needs, the need of other family members, as well as the needs of those who are unwell.

Each family member’s experience is unique; from the person they support to their specific responsibilities, no two family members are the same. Some family members provide continuous support for an unwell family member who lives in their home, while others may help someone with occasional periods of mental distress. Often, family members report going through a similar journey to that of their unwell family member. When their family member is not doing well, some family members report that they also feel unwell (this can come out physically and/or emotionally). On the other hand, when the unwell family member is doing well, the family member is often doing well too.

When thinking about your own mental health or the mental health of an unwell family member, it is important to recognize that good mental health is about living well and feeling capable despite challenges. People who live with a mental illness can, and do, thrive just as people without a mental illness may experience poor mental health. It is important for you to advocate for yourself and set boundaries. Family members need to take care of themselves before they can take care of someone else.

Make a Commitment to Yourself

It is easy to allow yourself to become engulfed in your unwell family members life and forget about your own needs. Being able to maintain an identity apart from your role as a family member is ultimately the best “medicine” for you both. Treating yourself well every day and putting your own well-being first will ensure that your mental and physical health is protected and that you are better equipped to deal with the demand of the family member role.

Taking a break requires a commitment to yourself and may also require planning ahead. You may for example, need to call on trusted friends and family to take a turn as family member for a short while. You may need to organize holidays and get someone to take your place when you are away. You may want to find out what services exist in your community for short-term caregiving. As hard as it may seem, there are many ways to take a break during the day. The first step is becoming aware of what it is that you find fulfilling or, at the very least, a good distraction. For some, going to work is a great way to get their minds off of things at home. For others, being involved in a church organization or playing with their grandchildren may be the answer.

We encourage you to take the time to ask yourself, “what am I going to do for me?” to take inventory of your interests and passions, and to build these things into your daily life. You may need time to reconnect with yourself, to remind yourself of who you are, what hobbies you used to enjoy, and the goals you once had for yourself. A journal can be useful to record your interests, hobbies, goals, and so on and to keep track of progress.

Some suggestions for ways to look after yourself include:

Make your physical health a priority. The stress of caregiving can take its toll on your body. Set aside time each day to exercise. Do whatever is possible – a 5-minute brisk walk with the dog, a 30-minute jog, 10 minutes of stretches, a round of golf, an exercise class at the gym, and so on. Make time to see your doctor if you need help with anxiety, stress management, sleep disruption, and any other issues you may have.

Look after your emotional and spiritual health. You may consider going to your church/temple/mosque or reading inspirational books. Some people find yoga or meditation helpful in developing mindfulness and being “in the moment”. Gardening or getting back to nature can be therapeutic for others. Positive affirmations can help focus on what’s right rather than what’s wrong.

Keep in contact with friends who can support as well as distract you. Resume your social life – for example, invite a friend to attend a hockey game, movie, lecture, and so on; or stay at home and invite a friend over to have coffee, watch the football game, or make a nice dinner together.

Attend weekly family support groups. Share your experience in a safe environment with others who truly understand what you are going through. Let yourself see that you are not alone in your struggles.

Maintain work if possible or take up a volunteer activity – for example, help at your kids’ school or preferred charity – to prevent engulfment in the illness and to provide valuable perspective.

Take a break; allow yourself to stop and do nothing. Consider the option, “Don’t just do something, sit there.” Treat yourself to a mid-morning “time out” with a good cup of coffee, sit in the garden, or listen to relaxing music.

Steal a few moments for yourself in the midst of your busy day – for example, take a few extra minutes to drive the scenic route home from work, enjoy a light conversation with your co-worker, slow your pace and look around you, or stop to pat the dog.

Above all, remain hopeful and expect success.

Family Caregiver Support

Parents: Trying Your Best, Despite It All

The unconditional love is always there, but it can be challenged beyond belief. Your heart is broken again and again because it hurts to see someone you love, suffer so much.

Destructive acts may cause you to actually feel hate toward your own child. And in between the love and hate comes fear, confusion, resentment, wonder happiness and guilt. We fear for our children’s future – will they ever be on their own? Will we spend the rest of our lives trying to help our children live normal lives? As much as we love them, we look forward to the empty nest. We must walk a fine line between letting our children learn from their mistakes and protecting them when a mental illness limits their capabilities.

Working with Health Professionals

Some parents are intimidated by mental health professionals. Keep in mind that they’re working for you. Respect their position and expertise, but don’t assume that they will always know best. Listen to clinicians with an open mind, even if what they say is something you wouldn’t want to hear, or it seems to be critical of you. Pay attention to your inner voice and assert yourself when you feel it’s necessary. The final decisions are always yours.

Remember, you are doing the best you can, and any success is worth celebrating.

Effects on Siblings

It is common for siblings to feel starved for parental attention until they cry for help with disruptive behaviour of their own. Parents should be aware of how the intrusive behaviour of one child might threaten the security of another. Boundary violations may be subtle, or, at worst, may extend to physically abusing a sibling.

Options for Support

Understanding and acknowledging your feelings, as uncomfortable as they may be, is important. Explore where they are coming from and how best you can deal with them. Many have found it beneficial to join a support group or speak with someone else who is also dealing with mental illness. Counselling may also be helpful. Over time, most are able to come to terms with having a loved one living with a mental illness and move on with their lives.

More Information:

- Families Matter Support Group (Registration Required)

- FROMI – Friends and Relatives of People with Mental Illness (No Registration Required) Please contact fromisk@gmail.com or 306-933-2085; 306-220-7748.

- Family Service Saskatoon – Programs for parents, families and children.